Another week spent dodging ever more dire warnings about the state of Scottish football.

This time everything's got a lot Grimmer with Aberdeen losing a lauded protégé to the mysterious land of riches that some people call England.

Highly rated youngster leaves Aberdeen area to chance his arm in England? If Jack Grimmer turns out to have a career like Denis Law's not too many Scotland fans will be complaining.

Still, it would be churlish not to concede that Grimmer's departure to Fulham exposes once again the divergence between football on either side of Hadrian's Wall. We're not so much the poor relations as the member of the family locked in the attic to save embarrassment.

Of course it wasn't always this way.

Not so long ago we could compete. Not only on the pitch but to an extent financially. Really, it wasn't that long ago.

Look back to Aberdeen in the mid-1990s. An Aberdeen where the memories of Alex Ferguson's achievements burnished even brighter than they do now.

An Aberdeen where signing a player for a million pounds wasn't some kind of bad Doric joke. An Aberdeen who did actually sign a player for a million pounds.

Hindsight. It's a wonderful thing.

Hindsight might tell Aberdeen that signing a player for a million pounds wasn't the sort of sustainable business decision they could afford to make.

Hindsight might tell Aberdeen that signing a player for a million pounds to show the Old Firm that there was still life in the north-east was folly.

Hindsight might tell Aberdeen that if you're going to sign a player for a million pounds you better make damn sure he's worth the money.

But hindsight is like finding the instructions after you've built the Ikea furniture. Which is why Aberdeen ended up paying a million quid to play a wonky wardrobe in midfield.

Paul Bernard.

The deal looked promising. Bernard was young, he'd built a reputation at Oldham and he'd already won two Scotland caps.

But something went awry.

Born in Edinburgh, Bernard grew up in Manchester and joined Oldham as a teenager. He made his debut in the 1990/91 season.

In just his second game he scored the equaliser as Oldham came from two down to beat Sheffield Wednesday and win the Second Division title on what we'd call a "helicopter Sunday" if it had been a Sunday and a helicopter had been involved.

That win, which denied Billy Bonds' West Ham a title they thought they'd won, saw Oldham back in the top flight after almost 70 years.

It also gave the young Bernard a ringside seat for an era of English football history: the Second Division Championship win gave Oldham a place in the last First Division, their survival ensured they became founder members of what was then called the Premiership.

In 1993/94 Oldham and Bernard were relegated, finishing second bottom on 40 points, ten ahead of bottom place Swindon but three away from safety.

That season he'd also featured in the FA Cup semi-finals as what Alex Ferguson described as a "dogged" Oldham took Manchester United to a replay before going down 4-1.

Back slumming it in the Football League Oldham faced some re-entry issues. 61 points wasn't enough for any more than a mid table finish as their away form - four wins and 13 defeats - dented any hopes of an immediate return.

Despite the reduced glamour of his surroundings - and fewer appearances than he'd managed in the previous two seasons - Bernard had made someone sit up and take notice.

Craig Brown was taking his Scotland team to Japan for the Kirin Cup at the end of the 1994/95 season and Bernard was on the flight.

A 22 year old in a Craig Brown squad might be considered something of a rarity and would probably not expect to play a major part in proceedings.

But Brown obviously saw the Far East as a place to experiment.

On 21 May 1995 Bernard, as he probably expected, took his place on the bench for a 0-0 draw with Japan that featured Jim Leighton as captain, Brian Martin and Rob McKinnon in the starting XI and a John Spencer red card.

Bernard came on for a 13 minute debut when he replaced Scott Gemmill.

Did he impress? Well, he certainly didn't do anything catastrophic enough to change Brown's mind about trying something different in the final game of the tour against Ecuador.

This time Bernard started in a reworked side and lasted the whole ninety minutes. His first full game was marked by a Scotland win: goals from John Robertson and substitute Stevie Crawford grabbing a 2-1 victory.

So it's the summer of 1995. Our hero - only recently described on an Oldham website as a "charismatic midfielder" - is now a full Scotland international and faces big decisions about his future.

He looks north.

Manager Roy Aitken had seen his transfer budget swollen by a share issue. Aberdeen, shaken by the sacking of Willie Miller and their apparent descent from the summit of Scottish football, needed to make a statement.

That statement largely involved making Paul Bernard the first - and still the only recorded - £1 million signing for a non-Old Firm club.

Did they actually pay £1 million? There are hints that so keen were Aberdeen to show their intent that the widely quoted figure was actually made up of both the transfer fee and Bernard's own signing on fee.

Whatever the truth, Bernard had the label: he was Aberdeen's £1 million pound man.

So drenched in despondency has the Aberdeen tale been of late it's tempting to say that Bernard was a disaster from the off. That's not true.

Aitken's side started well enough and even recaptured some silverware with a league cup win in November 1995. In what was Aitken's first full season they finished third in the league, pipping Hearts on goal difference.

They weren't ripping up the ground they'd lost on the Old Firm - there was a 28 point gap between Aberdeen and second placed Celtic - but they were offering hope for the future.

The million pound man was still just 23, Aberdeen looked to be on the up and European football was about to return to Pittodrie. Certainly Bernard's impact was somewhat muted but he had a lot to live up to with the price tag and he was acquainting himself with the Scottish game after serving his apprenticeship in different circumstances at Oldham.

Still, when Scotland travelled to Euro 96 the midfield maestro from the win over Ecuador was not part of the squad. If Bernard had thought a move to Scotland would increase his international chances he was mistaken: he was never to bother the Scotland team again.

His club career also faltered. Over 30 appearances in his first season at Aberdeen were followed by just 40 or so in the next three seasons.

What went wrong?

Injuries played a massive part. Maybe bad luck did as well. Perhaps the injuries contributed to a loss of form. Or maybe the pressure of being the million pound gem in a team that endured periodic struggles was too much.

If his first season had been underwhelming with hints of potential the next three were a disaster and the "million quid signing" tag became something of a Scottish football punchline.

He enjoyed a slight renaissance in 1999-2000, playing more regularly and scoring four goals - one of them coming in that memorable 6-5 away win over Motherwell when two Scottish international goalkeepers conceded 11 goals between them.

But Aberdeen were now under the control of the idiosyncratic Ebbe Skovdahl. With cost cutting to the fore and Skovdahl keen to mould his own team the end of the road had come.

Paul Bernard drove his Ferrari out of Pittodrie for the last time in October 2000.

The next stop was Barnsley where he went a season without a league appearance before joining Plymouth and managing fewer than a dozen games.

He returned to Scotland with St Johnstone in 2003 and appeared sporadically for a couple of years before a season with Drogeha United brought the curtain down on his career.

At 22 Paul Bernard had enjoyed instant success at Oldham, seen the dawn of the Premiership age, become a full Scotland cap and been the million pound signing who might just have ushered in a new era in Scottish league football.

At 33 he was retired: in a decade he'd barely doubled his career appearances, failed to add to his international caps and become a byword both for unfettered spending and an era of Aberdeen malaise.

He was probably quite comfortably off though which might just make this a very modern football tale.

A tale, all the same, of lost potential and, for whatever reason, of a talent squandered.

Forgotten Scotland Player number 12: Paul Bernard, Oldham Athletic. 2 caps.

Like this? Like the Scottish Football Blog on Facebook.

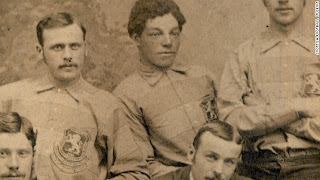

"I placed a Scottish saltire flag and a few flowers on the grave to commemorate his place in Scottish football history. But I have a strong feeling that Andrew Watson deserves more, a prominent and permanent memorial that truly recognises his place in sporting history as the first black international footballer, the first black administrator (he was secretary of Queen's Park) and possibly the first black professional player (at Bootle)."

"I placed a Scottish saltire flag and a few flowers on the grave to commemorate his place in Scottish football history. But I have a strong feeling that Andrew Watson deserves more, a prominent and permanent memorial that truly recognises his place in sporting history as the first black international footballer, the first black administrator (he was secretary of Queen's Park) and possibly the first black professional player (at Bootle)."